The French version of this interview was first published in ASUD #66

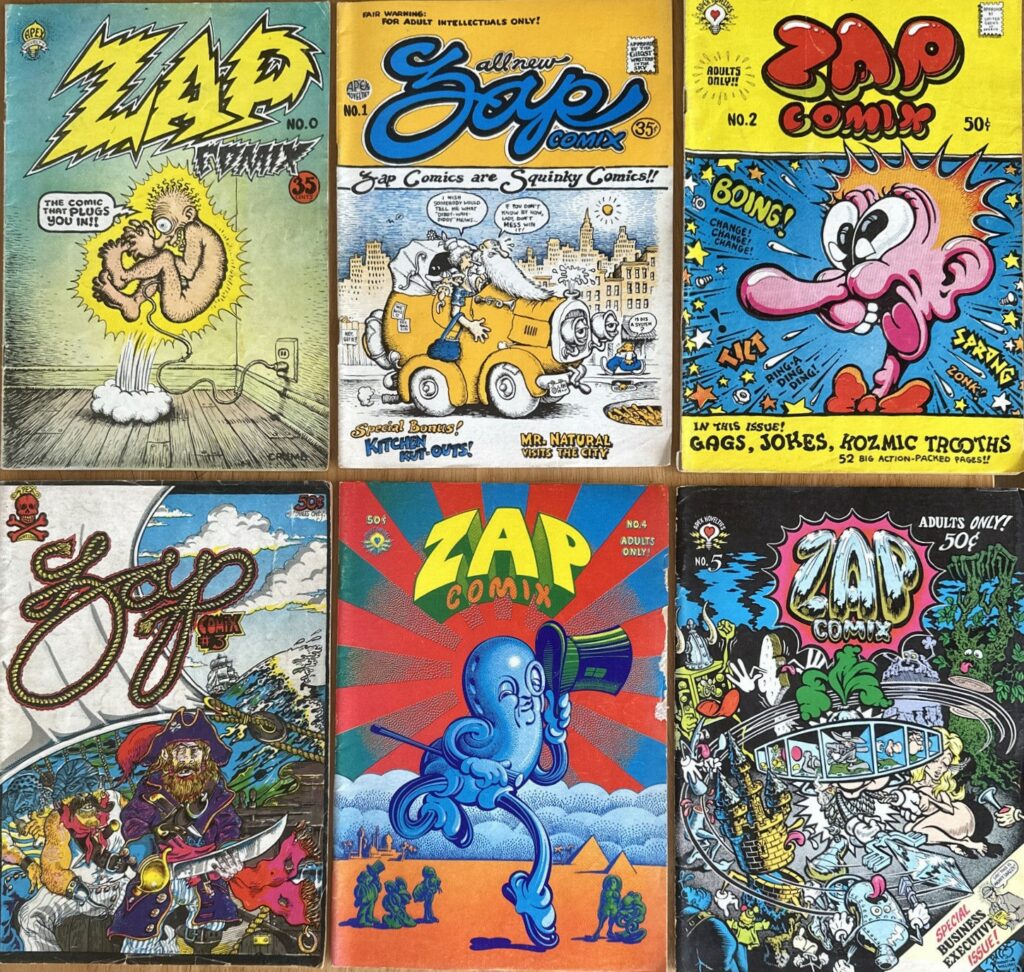

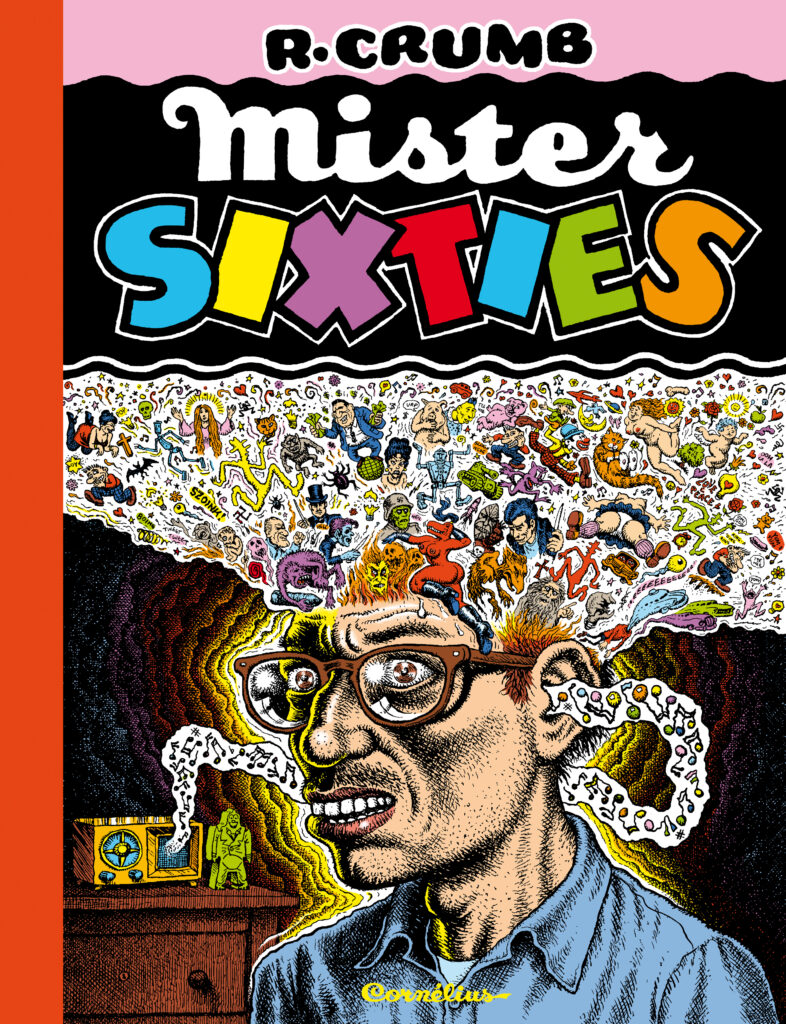

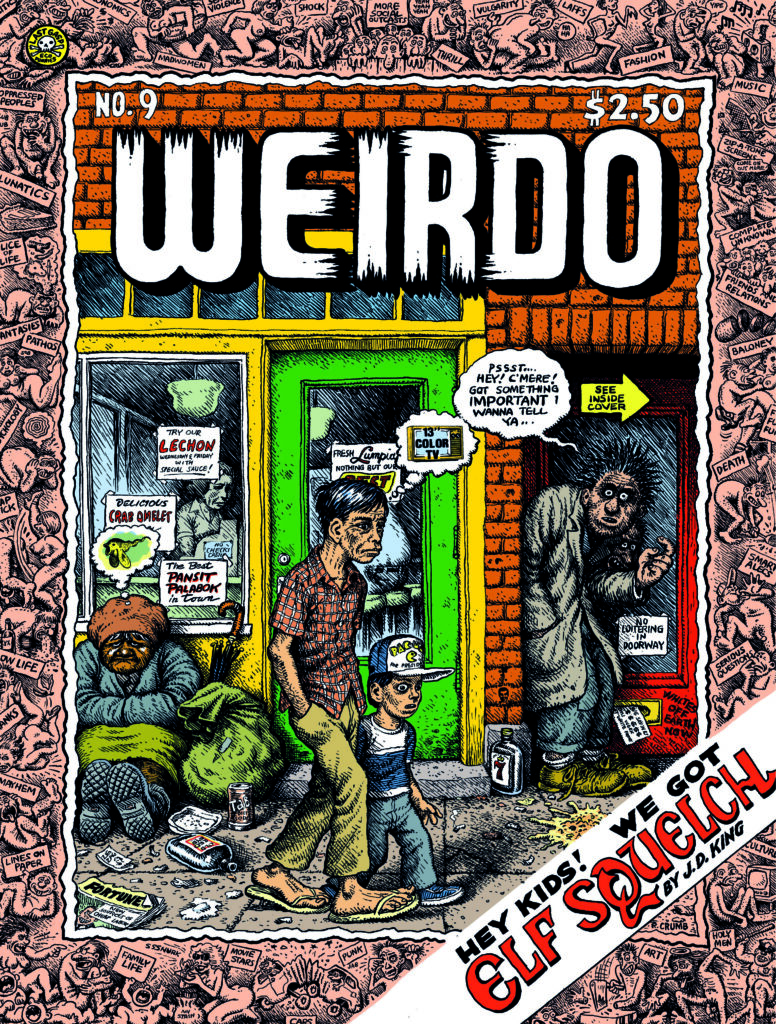

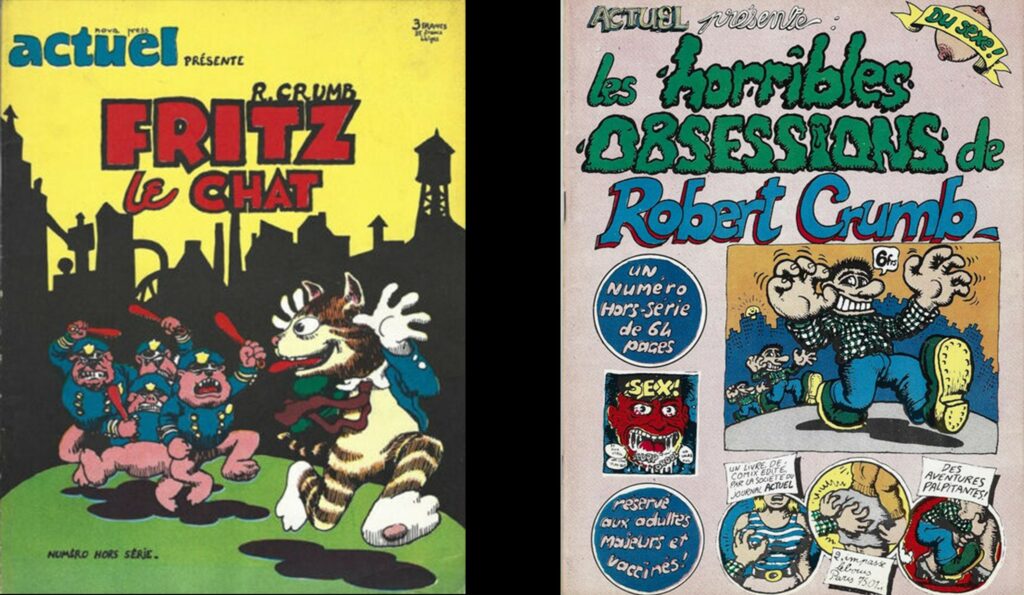

It is difficult to imagine the French underground art scene, if the comics of Robert Crumb weren’t regularly published in the Actuel magazine from the beginning of the seventies. Today, the creator of Zap comix, Weirdo, Fritz the cat, and other characters that inspired several generations of French artists, has been living in France for already 30 years.

Going through the paths of counterculture, outsider art, and the psychedelic experience, we will take the starting point of our interview with music, which was always an undeniable part of Robert Crumb’s life. Passionate collector of old jazz, blues, and folk records from his teenage years, he formed his own retro string band, named R. Crumb and His Cheap Suit Serenaders, in the 1970, where he sang lead vocals, wrote songs, and played banjo.

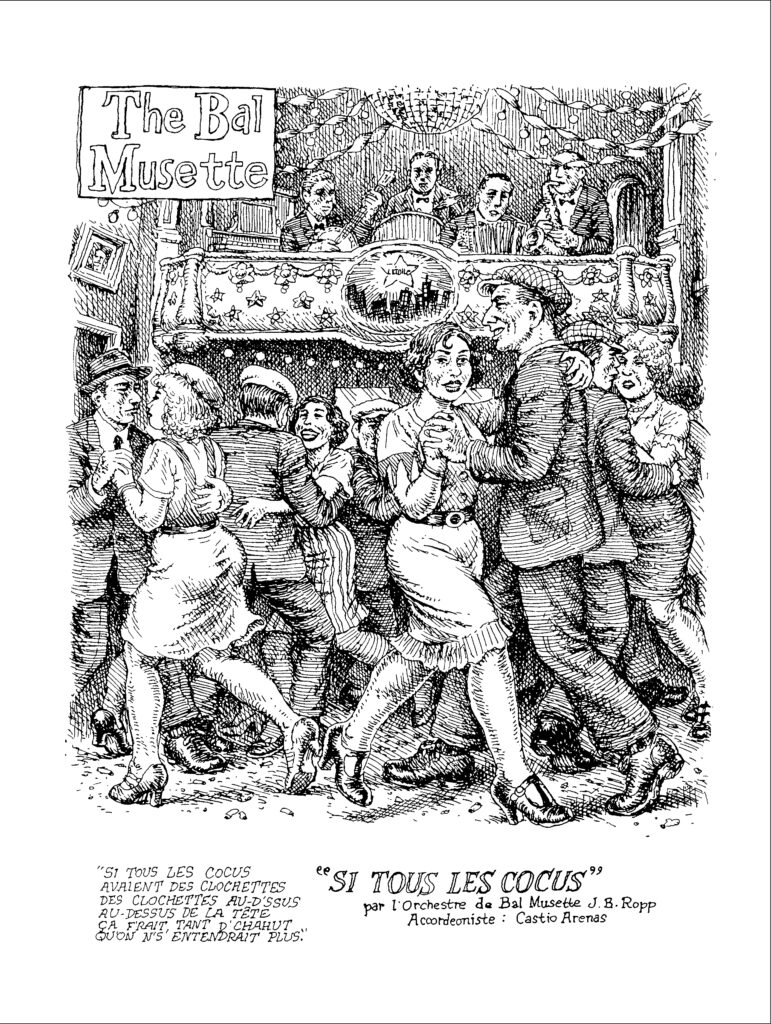

During his visit to the Angouleme festival in 1986, Robert Crumb met Dominique Cravic and ended up playing in Cravic’s folk, jazz, bal musette, and blues music band Les Primitifs du Futur. The same year they recorded their first album « Cocktail d’Amour » (1986). Since Robert Crumb moved to France in the beginning of the 1990s, they continued to play together regularly and recorded two other albums, “World Musette » (1999) and « Tribal Musette » (2008), for which he illustrated the covers. If Dominique Cravic was more interested in blues and jazz, Robert Crumb, a devoted researcher of forgotten musical genres, began to discover the French bal musette. His portraits of musicians of this old popular genre appeared recently in the book Les As du musette, compiled by Dominique Cravic and Christian Van den Broeck.

Besides his band with Dominique Cravic, Robert Crumb joins sometime Eden and John’s East River String Band, for whom he has drawn several covers of “Drunken Barrel House Blues” (2009), “Some Cold Rainy Day” (2008), “Be Kind To A Man When He’s Down” (2011) and the latest « Goodbye Cruel World » (2022).

Q. Besides art, you have also devoted a significant part of your life to music, collecting old-time records and playng with different bands. You said that drawing saved you. You needed to draw to make sense of a harsh world. What is different about the music?

Robert Crumb: Hard question to answer with words, these are two different parts of the brain. I think I have a deeper appreciation for music than for art, in fact. My older brother was very dominant when I was a kid, he made me take up drawing comics, and I became a comics artist. I aspired to be a musician, but got started all wrong. My whole life’s work has been drawing and art, but music is kind of my first love in a way. Music reaches very deep into me. When I hear music that I like, it gives me a kind of ecstasy that I don’t get with art. I am moved by strong visuals, but not as deeply as with music. I like to play music, but I never became a very accomplished musician, not like I did with my art. I am merely a second-rate musician.

Q. So these are two different parts of your life…

Robert Crumb: Two different parts of the brain, and I combine them often by making pictures of musicians or album covers for people if I like their music. Otherwise, I’m not interested. But art, for me, is a means of expressing my feelings about the world, both positive and negative, while playing music is a purely aesthetic pleasure, two very different forms of expression.

Extract from the concert of the Primitif du futur, with Robert Crumb and Dominique Cravic, at the Librairie de Paris in December 2023. The video is made by Céline Dumet-Oghia for the group Papiers Nickelés

Q. From the 1960s on, your drawings reflected modern American society, but you always listened to the music of the 1920s which connected you with eternity, as you said in the documentary “Crumb” (1994), you didn’t listen rock at all. Some of your comics were inspired by music, like “Keep on Truckin’” and “Mr. Natural” by a Motown song you heard on the radio. What was the connection between your drawings and the music of the 1920s you listen to?

Robert Crumb: Yes, I used to draw these sort of musically inspired comic strips. I did that when I was young. And now I’m doing drawings very meticulously, copying from photographs of old blues singers.

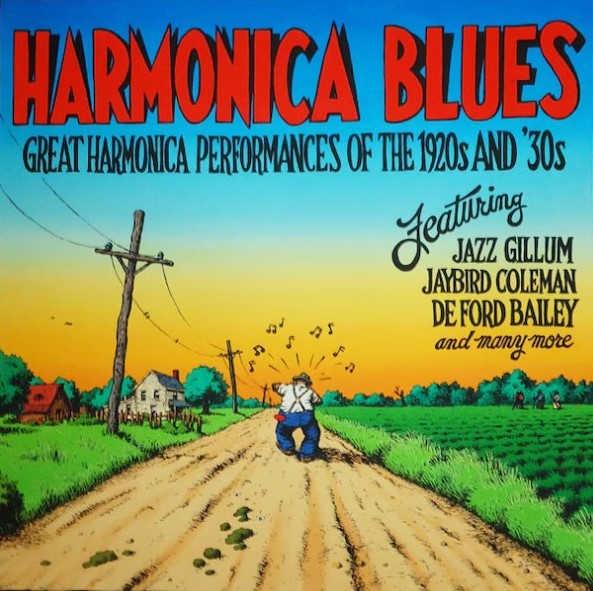

Q. In The Complete Record Cover Collection (2011), we can see some of your artistic interpretations of these old 78 records, including such Yazoo albums as “Truckin’ My Blues Away,” “Harmonica Blues” and “Please Warm My Weiner.” Usually in your cartoons you are drawing the surrounding reality that you observe, you make representations of the streets of modern cities, but when you were drawing those album covers for music of the 1920s, what inspired your image, what was the source?

Robert Crumb: Sometimes it was just what music evoked in my head. It was the romance of old-time music, the vision of a guy walking down a dirt road, playing harmonica in the countryside. But that was when I was young. I don’t do those romantic images anymore. Now I’m just copying from photographs.

Q. When you moved to France, you brought your collection with you. How many records do you have?

Robert Crumb: When I moved to France in 1991 I have something around twenty five hundred records; now I have 9,000. There’s no end to it. There are still plenty of good old 78s from the 1920s and ‘30s to discover. I recently came into possession of some incredible Ethiopian 78s, also a handful of Indonesian “krontjong” records, fine music, difficult to find. Not many of them ever made it to places outside of their own countries.

Q. You are impressed to discover new musicians. But are there artists who impress you today?

Robert Crumb: Yeah, sure. All the time. Always some interesting new young artists coming up all the time from France, America, and other places. I just recently, a couple of years ago, discovered this young Swiss woman artist, Simone Baumann, from Zurich and she’s great. My favorite French cartoonist was this guy named David Sourdrille. He did some very fine work. I don’t know if he’s still working or not, a sick, twisted artist, a man I am in complete sympathy with.

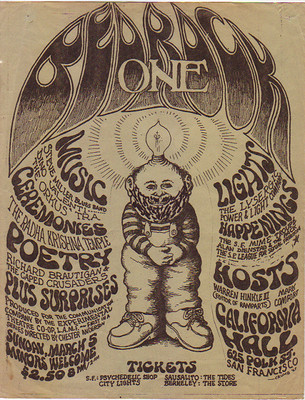

Q. You were close with the creators of the psychedelic posters, Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso, who were published in Zap Comix. But once you also made a psychedelic poster for the March 5, 1967 concert, “Bedrock One.”

Robert Crumb: That’s my only printed psychedelic poster.

Q. Why did you do it if you didn’t like rock music?

Robert Crumb: Well, I was very inspired by those rock posters; they were what motivated me to flee Cleveland and go to San Francisco in January, 1967. S. Clay Wilson and I were looking for work that summer. We needed to make some money. So we went to the Family Dog which was one of the entertainment companies that were producing rock concerts. Family Dog’s main venue was the Avalon Ballroom. It was run by a guy named Chet Helms. We showed him our work, and he said, “Nah, we already have enough poster artists. We don’t need any more.” But Chester Anderson, who did that Bedrock concert, he’d seen my work somewhere, came to me and asked me if I would do that. It was not a big poster, it was just a little black & white flyer, very crudely printed, very disappointing, actually.

Q. So you didn’t want to repeat this experience?

Robert Crumb: Well, nobody was asking. There were lots of poster artists and a lot of artists wanted to get in on the action because those guys — Griffin, Moscoso, Wes Wilson and Stanley Mouse — were like rock stars themselves. And after Griffin and Moscoso became part of Zap Comix. I remember the first couple of issues they were involved in, we’d show up at the printers with our work, and Moscoso would be wearing a velvet jacket, he looked like a rock musician. And he’d walk into the printers and they would treat him like royalty, like he’s a big celebrity in the rock poster scene. So they really thought of themselves like rock musicians.

But the whole psychedelic rock music scene didn’t interest me at all. Musically, it didn’t do anything for me. I tried, I went to concerts at the Fillmore Auditorium which was operated by a character named Bill Graham. It was all psychedelic noodling on electric guitars. They played too loud, and they had the strobe lights going. I remember seeing people who would, like, have a seizure from the strobe lights and fall on the floor, writhing around. You know, it was supposed to be an all-encompassing sensory experience, the music, the light show, the strobe lights. I never hung around very long. It kinda just made me sleepy.

Q. Even if the psychedelic posters of Moscoso, Griffin and your cartoons were inspired in some way by the psychedelic effects of LSD, stylistically the posters are different, very colorful and inspired by Art Nouveau, and they are devoted to the rock that you didn’t like. What made you close to these artists?

Robert Crumb: I thought the posters were very inspired work, very innovative with imaginative lettering styles which at the same time harkened back to old time American graphics. And it was obvious just from looking at them that these artists were taking LSD. And then, they wanted to do comics. S. Clay Wilson and Moscoso and Griffin were very impressed with the first issue of Zap Comix, which came out in early 1968. They came to my house to meet me, and they were interested in doing comics and I said, great, let’s do ZAP Comix together. And that worked out very well for a while. But then the comics scene started to flower and grow. There were a lot of new interesting artists turning up — Justin Green and Kim Deitch and Spain and all those guys. After Griffin, Moscoso, Wilson and Spain Rodriguez came in, Gilbert Shelton and Robert Williams came in to ZAP Comix too. And so, there were seven of us in ZAP Comix. And after that, they didn’t want ZAP to be open to any other artists. I thought that was not a good idea, and then we couldn’t get it out very often, because Moscoso would always take a very long time to do his work. So ZAP Comix was only published every couple of years. So I lost interest in ZAP Comix. I didn’t think we were like a band, we were just a bunch of very individual artists. I said to them, “Look at Justin Green’s work, it’s great, let’s put him in.” No, no. “Kim Deitch”. Nope. And then I wanted to put Aline in. They said: Oh no, no way. But I finally got Aline into that last issue of ZAP Comix #16, I think I used these collaborations that we had done for the French magazine, Causette. So I put some of those strips in there, and Moscoso said, “Crumb’s pulled a fast one. He got Aline in ZAP, snuck her in the back door.” But that was the last issue of ZAP, number 16, which took ten years to complete, and finally came out in 2016. Sixteen issues in 48 years! Could’ve been a lot more if those guys had been more open. It was very disheartening, to see these creative artists suddenly become so exclusive. And then they accused me of being a snob when I didn’t want to do ZAP Comix anymore! Ironies of life. It’s all water under the bridge, ancient history by now.

Q. You said that you were never close to the hippies.

Robert Crumb: Did I say that?? I was not stylistically a hippie. I didn’t like the music. But I took the drugs and had psychedelic experiences just like all the other hippies. And I was in the scene, I lived in Haight Ashbury and all that, but I just didn’t embrace all of the stuff that they were interested in, especially the music. I made some effort to fit in, largely because of all the beautiful young hippy girls. Oh my God, some of my hippy male friends were picking up new young 17-year-olds arriving in Haight Ashbury every day. I didn’t know how to talk to those girls. I was very shy.

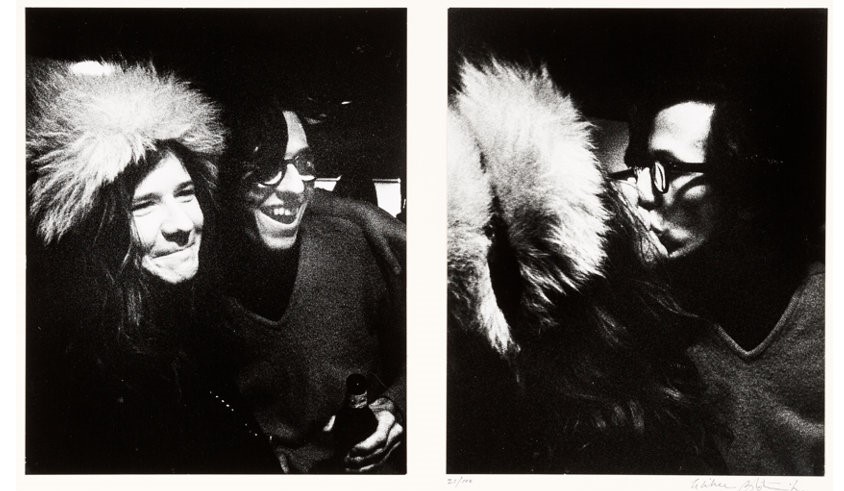

Q. But Janis Joplin, the iconic figure of the hippie music scene, was one of your friends.

Robert Crumb: Yeah, I liked her singing, but I didn’t like that band she was with. And then I later heard some tapes of music she did before she got into rock and roll. She was singing with a country string band, singing hillbilly music. It was great. Much better. She was much more suited for that old-time type music. But she got lost… She became a star. She drank too much and took too many drugs and was getting bad advice from agents and record producers and ended up in 1970 dead in a hotel room, face down in her own vomit. 27 years old.

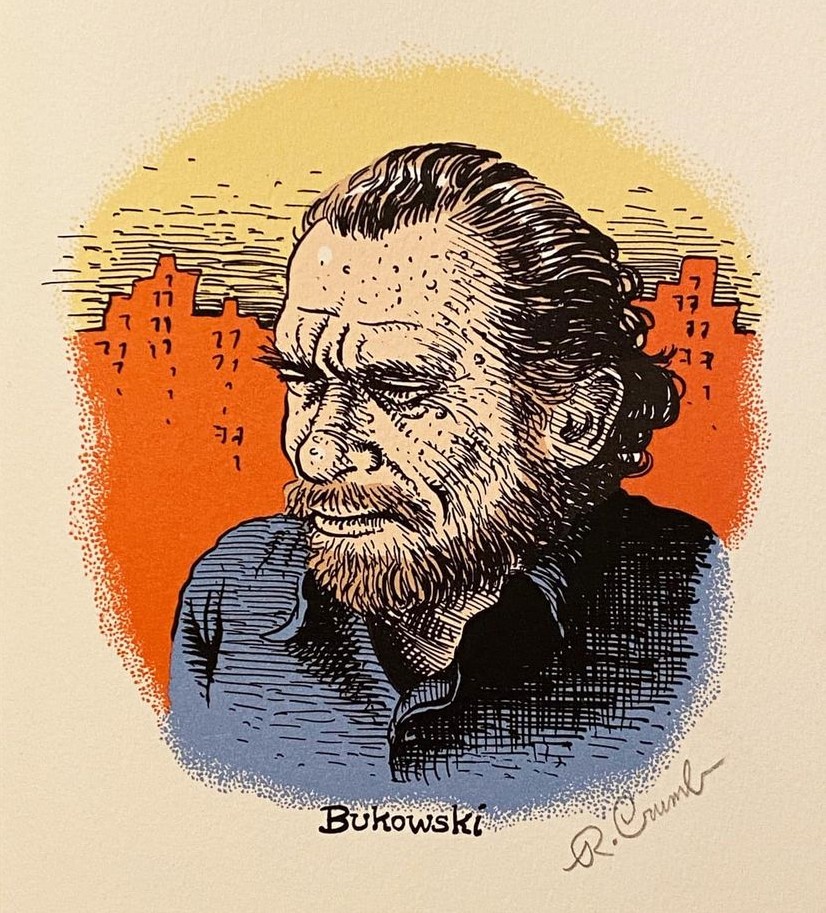

Q. In 1972, you met Charles Bukowski in Los Angeles, and his vision of reality is rather close to yours. Can you tell me more about this encounter?

Robert Crumb: Yeah, I liked his writing. It kinda resonated with me. As for my encounter with him, it wasn’t very long. All he said to me was, “You’re good, kid. Just stay away from the cocktail parties.” What he meant was, stay away from the pretentious bullshit scene. He advised lots of young writers and artists to remain isolated from the culture scene. It’s just a big waste of time. Those people are impressed with your work. They invite you to parties; they send you free plane tickets to fly to New York. It’s very seductive. And at the same time, that’s where the money is. So you have to dance around these people somehow. You know, what Tom Wolfe called the “boho dance,” the bohemian artist’s relationship to the bourgeois, because they’re the ones who support you. You are in rebellion against the bourgeoisie, yet you need their support. A tricky business. Some artists have an extra knack for this game, others don’t. It has nothing to do with how talented or original you are.

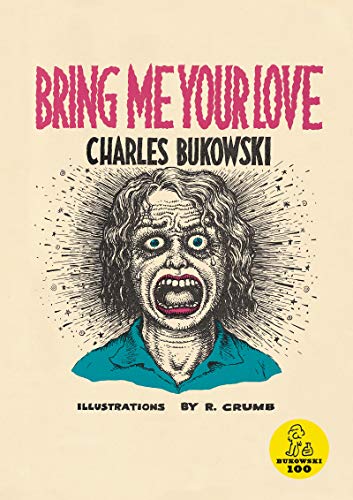

Q. In 1980s, you illustrated two short books by Charles Bukowski (August 16, 1920–March 9, 1994), Bring Me Your Love and There’s No Business. How did this collaboration come to life?

Robert Crumb: It was John Martin’s idea. John Martin ran Black Sparrow Press that produced Bukowski’s books at that time. He came to me and said, “I like your work, and I think you and Bukowski would be a good fit.” So yeah, I was a big fan of Bukowski’s work. But I never hung around with him, he was a hostile drunk. Once I went to a party thrown for him after a reading he gave in San Francisco. He was just drunk out of his mind. And there were two women whom I knew, Susan and Jane, they took Bukowski each by one arm and led him staggering into a bedroom and closed the door… I was jealous. Why couldn’t it have been me? At least I was sober.

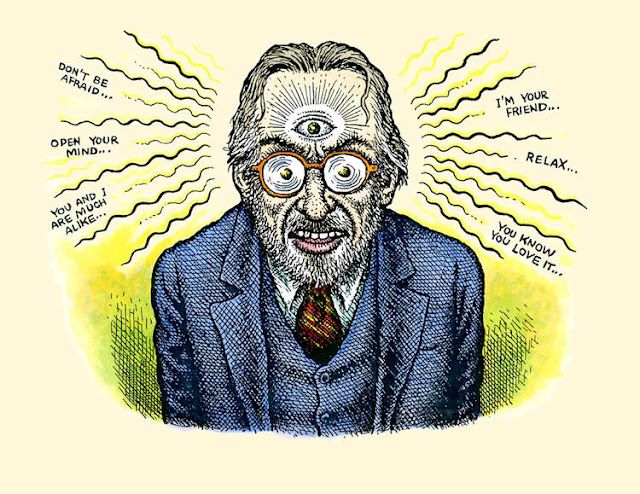

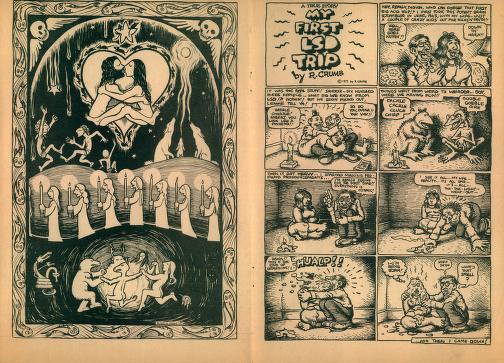

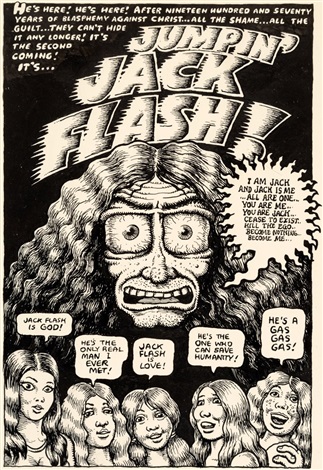

Q. Many of your characters, Mr. Natural, Shuman the Human, Flakey Foont, Eggs Ackley, were created after an LSD experience you had in 1966. Your style changed, became more round, stretched, the characters became too big or too small, and during that time the rhythm of yours comics was very stream of consciousness. What impact did LSD have on your perception of reality?

Robert Crumb: Taking LSD changed me deeply. My whole perception of what I was doing changed. A powerful LSD experience completely breaks your ego down into atomic particles and, so of course you see everything differently. Everything is put into a different perspective after you do that. And that was very good for a while, for several years. There was less ego interference in the work, just working more intuitively. At the same time it made dealing with the practical necessities of life more difficult. I was “spaced out,” as they used to say.

Q. There is a book by a professor of Yale University, Charles A. Reich, The Greening of America (1970), talking about Stoned from Head Comix, in which he underlines the importance of your texts which reflect the consciousness of modern society. But what importance do you give to your texts ? Was your writing also affected by the LSD?

Robert Crumb: I can’t separate the text from the pictures. It affected everything. My approach to text, my approach to the drawing, was all changed by LSD. And then the LSD effect wore off by the end of the 1970s. I stopped taking LSD in 1973. A voice in my head told me “You don’t have to do this anymore.” That last trip was awful, in summer of 1973, I had a vision of the future of the world that was not good. It was very hard, this vision of the way the world was going. And, too, with LSD in those days you were never sure of what you were getting, they were putting all kinds of crap in LSD, like amphetamine, for instance. So with the LSD,you always took your chances. I had to stop doing it. By the end of the 1970s, I was kind of trying to find new sources of inspiration, but the LSD-inspired period was over. Then I started Weirdo in 1981. Times had changed and so had I. Even if the 1980s were tough, I did a lot of work in those years, and when I look at that work now, though it’s quite different from the ‘60s-‘70s period, I think it had its own charm.

Q. You participated in the book El Perfecto to support Timothy Leary. Was it a true bad trip story for this book?

Robert Crumb: Yes, it was a true story. It was my first LSD trip, taken in June ’65 with my first wife, the long-suffering Dana, God rest her tormented soul. I threw up in her face. But I almost always threw up when I took LSD. It was always both good and bad.

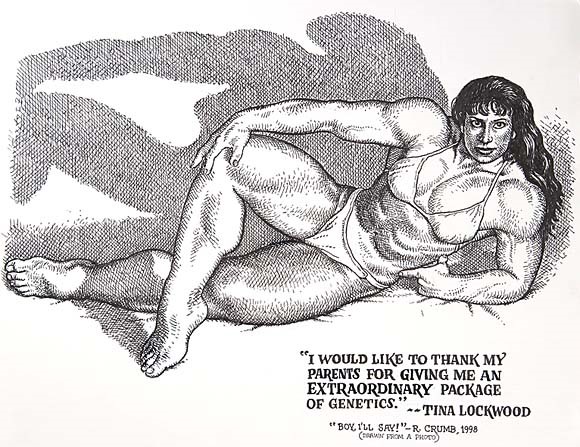

Q. You have always drawn powerful, strong women in your cartoons. In the 1960s, when you began to draw, women didn’t have the strong position in society that they have today. What made you create these characters? When you were a teenager, you were attracted by the TV character of Sheena: Queen of the Jungle, but you continued to draw this kind of woman for a longtime…

Robert Crumb: Basically, it’s just a life-time sexual fixation on big, strong women. But when I was young I had “anger issues” with women, so all that violent craziness came out in the comics. When I was doing these comics, I had no idea what purpose these comics would serve. I wasn’t thinking about that, I didn’t think about who was the “target audience” for my comics. Nor did I ever aspire to be a mainstream cartoonist with a mass audience. In fact, I was sorta crazy. Even so, I had some kind of modest following for my crazy comics, from which I made a modest living, completely on my own terms. Wow! The gods smiled on my sorry ass!

Q. Your comic zine Weirdo focused on individuals who felt like outsiders. I think there are many people who do not feel connected to normal reality. Maybe they could find themselves while reading your comics.

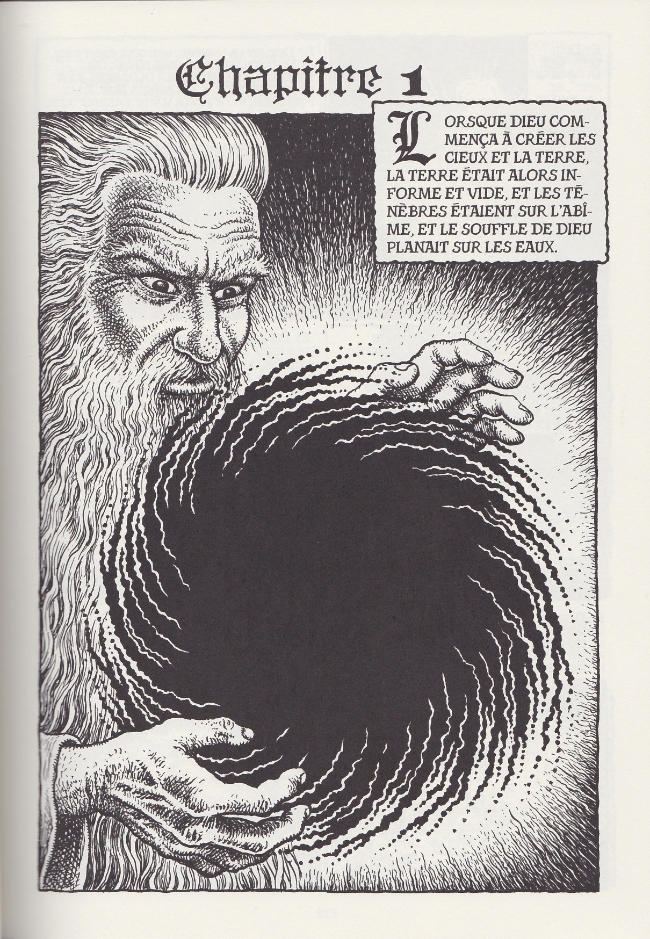

Robert Crumb: Maybe some people did, I don’t know. At least they knew they weren’t not alone. But the biggest selling book I ever did that actually made some money was The Book of Genesis. Outside of that, the audience for my comics was always quite modest. My stuff is generally too quirky and weird for most people. The Book of Genesis, on the other hand, sold hundreds of thousands of copies! The publisher was totally amazed. What made my Book of Genesis different from the rest of my work? The answer is quite simple: it’s the Bible! And I did it as a straight illustration job. I refrained from making fun of it.

Q. However, you were very popular in France already in the 70s. Your comics were first published in France by the militant journal Action in 1969. After, in the beginning of the 1970s, they were published in Actuel by Jean François Bizot, who popularized the counter-culture in France. Can you tell me about your first encounter with him?

Robert Crumb: All I remember about it is I was in Chicago, I think it was 1969. I was visiting my friend Marty Pahls there, and Marty was living in a basement apartment under the street. There was a window in the salon that faced out onto the sidewalk. It was summer and it was hot, so he had the window open. I’m sitting there talking with Marty, and this guy climbs in the window and introduces himself : “Hi, I’m Jean-François Bizot from France.” He said he wanted to use my work in his new underground-style paper, Actuel. I told him it was fine with me. Things were loose back in those days.

Tout ce dont je me souviens, c’est que j’étais à Chicago, je crois que c’était en 1969. Je rendais visite à mon ami Marty Pahls là-bas, et Marty vivait dans un appartement au sous-sol sous la rue. Il y avait une fenêtre dans le salon qui donnait sur le trottoir. C’était l’été et il faisait chaud, alors il avait la fenêtre ouverte. Je suis assis là à parler avec Marty, et ce gars grimpe à la fenêtre et se présente : « Salut, je suis Jean-François Bizot de France. » Il a dit qu’il voulait utiliser mon travail dans son nouveau journal de style underground, Actuel. Je lui ai dit que cela me convenait. Les choses n’étaient pas claires à l’époque.

Q. Jean-François Bizot was a member of Underground Press Syndicate, so he could publish your drawings for free.

Robert Crumb: Yes, there was an agreement that everybody in the Underground Press Syndicate could share each other’s articles. There was a lot of my work in Actuel for about five years. This was my major exposure in France back then.

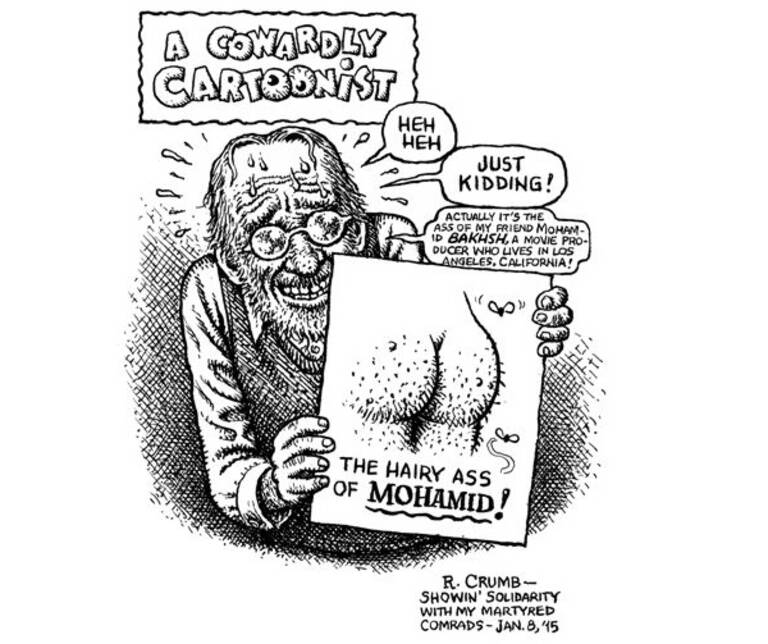

Q. You almost never turned to French modern reality, only once you made a drawing for the journal Liberation after the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo. But in your last book Les As du musette, you made the illustrations of French musicians of the first half of the 20th Century. Why did you turn to this period?

Robert Crumb: I made Those drawings in the 1990s, it was a little box set of cards of these accordion players. Nobody in France was interested in buying them. I sold more in the United States to Crumb fans than I did in France. It is kind of crazy. Some of those musicians that I drew had never been reissued, they were only recorded on 78 rpm. A handful of people knew who those guys were. But since I love old-time musette, I was inspired to do the drawings of the musicians, plain and simple. It was an utter commercial failure.

Q. But do you think about the current French reality?

Robert Crumb: I moved to France when I was 47. So I’ll never truly be able to grasp what’s going on in their heads the way I can read Americans or understand America. My family, the Crumbs, came to America in the 1600s, so I’m deeply American. But I like living in France, it’s really a nice place to live. France is a considerably more civilized country than the United States. The United States is still a very wild, barbaric country. That makes it interesting, but it’s tough. Hard to live there.

Robert Crumb’s tribute to the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo, who were murdered on January 7, 2015. The drawing was published in Libération in 2015.

Q. The USA brought us the beatniks and the counter-culture of the 1960s, with the free press and the hippie movement. However, we already saw a decline in this culture in the seventies. What, in your opinion, was the reason for this decline? The disappointment or commercialization of this culture, or something else?

Robert Crumb: There was a cultural revolution in the United States in the 60s. And the older generation couldn’t believe it. They thought that these young people, the hippies, must have landed from Mars! They didn’t understand what was going on with them: “Why are all these middleclass white kids just throwing away all these opportunities that we have worked so hard to give them? We grew up during the Depression. We fought the war for them, we created all this material prosperity, and they’re just throwing it in the trash. What is wrong with them?” And this happened because the world that they offered us was empty, it was material prosperity, materially comfortable. But it was it lacked substance, and above it all stood the insane threat of nuclear annihilation.

By the end of the 60s, many young people wanted to join the hippie subculture because it was… “sex, drugs and rock and roll.” It started with the beatniks, which was an intellectual stance. It was a very left wing, socialist, communist rejection of capitalism and materialism and the nuclear standoff with the Soviet Union. I grew up in the 50s and 60s thinking that at any moment there could be World War Three. They could be dropping atomic bombs on us at any moment. That discredited my parents’ generation, because they accepted this. So then psychedelic drugs were introduced on a wide scale, Timothy Leary and so on. We took LSD and were pushed even further out, we wanted to start over completely, go back to the land, grow our own food, completely start over with a whole new set of values and ethics and everything, start from the ground up. At the same time, the government and the people in power and authority did everything they could to oppose this movement, to subvert it, to undermine it in every way they could. The hippies wanted to start communes out in the countryside and “do their own thing.” And they were constantly harassed by officials and the local sheriffs and the departments of health. You can’t do this! You can’t build your own shacks! You need building permits! You can’t just go off out into the country and do whatever you want. It’s not permitted!

The drugs had a lot to do with the decline of the counterculture because people just mostly wanted to get high and have a good time. They didn’t care if they were living in squalor. There was a strong hedonistic aspect to the hippie subculture — sex and drugs and rock and roll. I remember in the 70s, in this commune we tried to do in California, where everybody just sat around smoking dope all day, and who was supposed to do the work? There was big talk of growing our own food, but somebody is supposed to be out there hoeing the ground. It’s a huge amount of work growing your own food, it doesn’t just sprout up on its own. You have to dig these rows and plant and water it, you have to pull the weeds. Who’s gonna do it? People just wanted to get stoned because they were mostly middle class kids. They didn’t really have the will to put in the sweat, everybody seemed to feel that we’re the beautiful people, we don’t have to do anything. It’ll all be taken care of somehow because we’re so beautiful and enlightened.

At the end of the 70s, you had the rise of the punk culture, which showed complete disgust with the whole hippie scene. They were younger than us and they understood that actually, the world is a rough place and you can’t survive on just being sweet and gentle, sitting around playing your guitar.

And then in the beginning of the 80s, you get the rise of the yuppies. The yuppies were all about, let’s get back in the money game, take your education seriously, go back to school, become a lawyer, become a professional, claw your way up in the financial world or start your own business. Then you had the rise of the tech industry and so that was pretty much the end of the hippy counterculture. But the counterculture movement had a permanent effect. Things never went entirely back to how they were in the 50s.

Q. I believe there will always be outsider artists resisting social constraints.

Robert Crumb: Yeah, of course. Basically, an anti-bourgeois stance has existed since the bourgeois began to rule with the Industrial Revolution. With the Industrial Revolution, we got a money-based world, and money makes people culturally extremely conservative. They started wearing black suits and very stiff collars and everything, the music became very conservative, and art too. So the people who felt suffocated by that rebelled against it. They developed a bohemian subculture in the 19th Century in Europe, there was a very strong bohemian subculture in France. Today we have outcasts and weirdos doing all kinds of strange, demented works of art. There are the permanently maladjusted kind of artists. They remain isolated and produce something that’s real. But we also have artists who are very adept at doing the Boho dance, the hustlers in the fine art world. Their whole thing is to sell their art for lots of money. People that produce their own zines and stuff, they know that they have to have some other job, some other way to make a living because they are not going to make money off their zine. This is where most of the interesting art comes from in our time, in this underclass of real outsiders. You will rarely see it in big, posh art galleries.

Q. What do you think is the best way to balance freedom and earning a living through your art?

I got no solution, but I was lucky somehow. You know, when I first started doing comics, it was all still about the traditional printing, distribution, retail outlets — all that stuff. Somehow, I was able to make a modest living. Through the 80s, we lived very modestly, Aline and I. The publishers didn’t pay much. Weirdo made zero money. But then my original artwork started becoming valuable in the fine art world. I didn’t promote my work to them. The fine art world came to me and wanted to sell my original artwork, and so the value started going up. I have lived very well on the sale of my original art, not from the publications, except for Genesis. Genesis is the only book that paid well, but otherwise my work is too weird and eccentric for the mass market.

Q. In any case, the artists who make underground comics don’t think about making money with it. As it was for you, their work is a kind of connection with reality or creating another reality, their own reality.

Robert Crumb: It’s only been since the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the bourgeoisie that sensitive people needed to make art out of their alienation. That didn’t exist earlier, in the time of Bruegel or Bosch. If you were a skilled artist in Germany in the 1500s, you made popular prints, etchings, engravings of peasants vomiting or a wife catching her husband with another woman and beating him on the head. This was popular entertainment, these guys were craftsmen, they didn’t feel alienated. If you were alienated in those days, you got yourself to a monastery where you sat all day rendering illuminations for those beautiful illustrated hand-lettered books. That’s what I would have been doing if I were living in a 1300s. I’d be sitting in a monastery doing those illuminations, the little ornate flower patterns around the lettering.

Q. Today, we are discussing ‘outsider art’ as a separate category of art, but outsider artists have always existed.

Robert Crumb: Of course, there was always crude art. Going way back to the 1500s, from the beginning of print, there’s a whole genre of crudely done prints that are really interesting to see – hard to find, though. Now just look at this weird art by an eccentric guy who lived isolated somewhere in some small town in America. It wasn’t even called art. It wasn’t called anything. It was just weird. My brother Charles was committed to a mental institution in 1971. He spent a year there because he tried to kill himself. When I went to visit him at this state-run asylum, I noticed that they had a display on the wall of drawings tacked up, made on pieces of notebook paper. The drawings were made with children’s crayons or ballpoint pens or anything they had at hand It was one of the best art shows I ever saw. You know, just art by crazy people. It was great! to draw with. It was authentic, it was for real. They were expressing some strangeness in their mind that was very revealing, very inspiring to see.

Q. Actually, Saint-Anne psychiatric hospital in Paris has a museum where they organize the exhibitions of their patients.

Robert Crumb: They do?

Q. Yes. Sometimes the British magazine Raw Vision asks me to write about the exhibitions of their patients. But now there are museums dedicated to this kind of art. These artists are often shown at the Halle Saint Pierre in Paris, but there are also many other museums as the Sammlung Prinzhorn Museum and the Collection of Art Brut of Lausanne.

Robert Crumb: The problem is that we live in a money-driven society. You can’t artificially create outsider art. People are trying to do that now because it’s a thing. So there’s fake outsider art now. If it’s just a crazy person in an institution, that’s not about the money. That’s just about some way of making a drawing expressing this nightmare in your mind. So outsider art is sort of a threat to the art establishment. Today, there is like a competition, the critics and galleries promoting works of art to make them more valuable, to make them worth big sums of money. They are exchanging hands for millions of euros, millions of dollars.

Images credit: © Robert Crumb / Cornelius

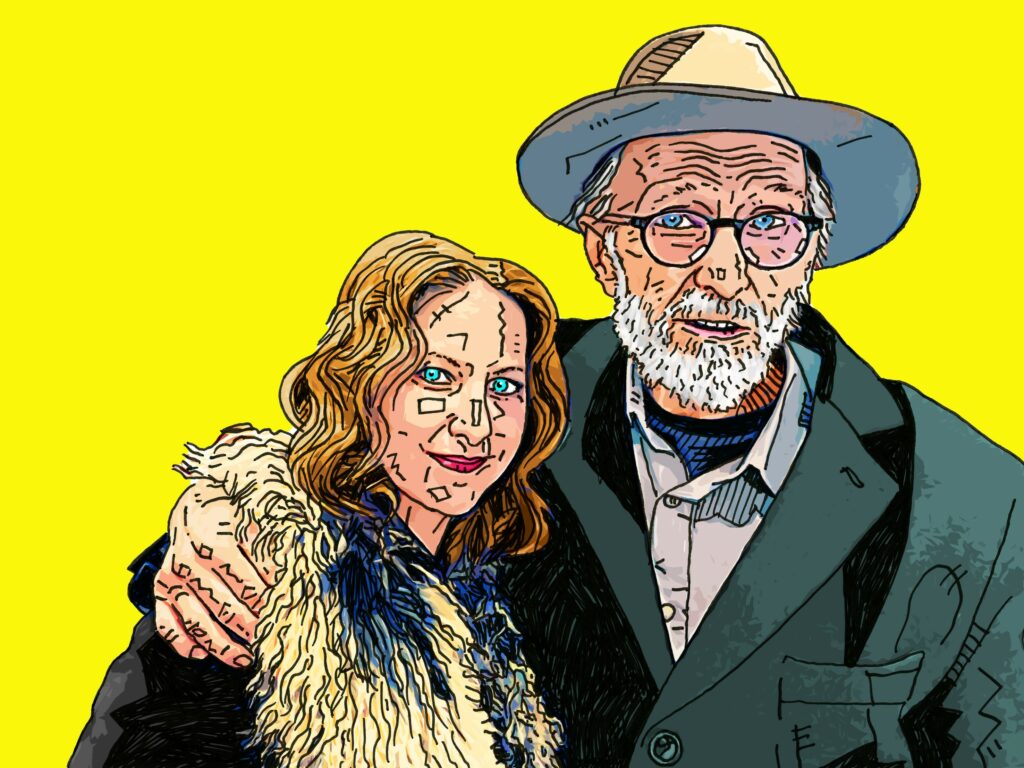

Robert Crumb and Alla Chernetska by Kiki Picasso, after the photo by Dominique Cravic, 2023

I would like to thank Dominique Cravic for his invaluable support in the realization of this interview